Creating maps with Geopandas

The last few week I began playing with creating maps in Python using the Geopandas library. It’s an amazing tool and I’ve become a big fan. The syntax is very similar to Pandas, and it works brilliantly with matplotlib too. To be honest the jump from using Pandas to Geopandas is tiny, and if you are comfortable with Pandas, there isn’t much work at all to understand Geopandas.

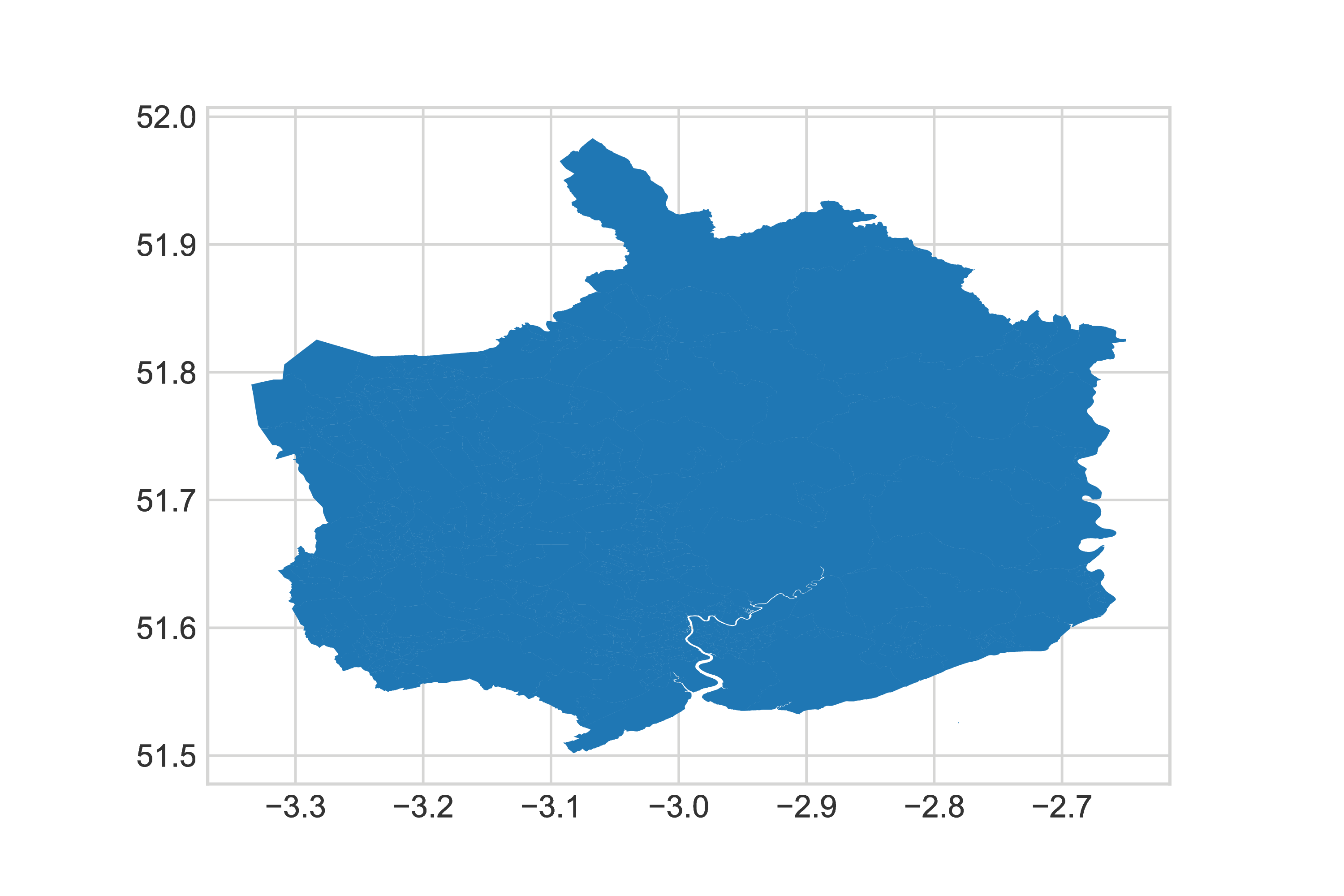

As part of my PhD work I looked into deprivation level in the five counties served by Aneurin Bevan University Health Board. I had a lot of help understanding LSOAs, polygons, and WIMD scores from my brother Rob who had produced these types of maps before in R. In this post I’ll show examples of plots I’ve created, and the simple code used to produce them.

Downloading Data

In my work I concentrated on five counties in south east Wales: Blaenau Gwent, Caerphilly, Monmouthshire, Newport, and Torfaen. I also needed to look at smaller more detailed areas. The smallest category of area in Wales are LSOAa (Local Super Output Areas), which are areas were between 1000 and 1500 people reside. Each LSOA has a code and a name: for example the LSOA containing Chepstow Castle is “St Mary’s”, and its code is W01001587.

In order to map LSOAs we need to know the shape and position of each area. These are defined by polygons. You can download these is geojson format from the ONS. Here’s the link that I used, which contains all LSOAs in Wales and England:

(Note that this dataset is huge: 34,753 LSOAs, each containing every vertex of the polygon that defines it. This will take a long while to download, ad will take some time to open with Geopandas. The first thing I did was filter and save another geojson file containing only the LSOAs of the five counties of interest.)

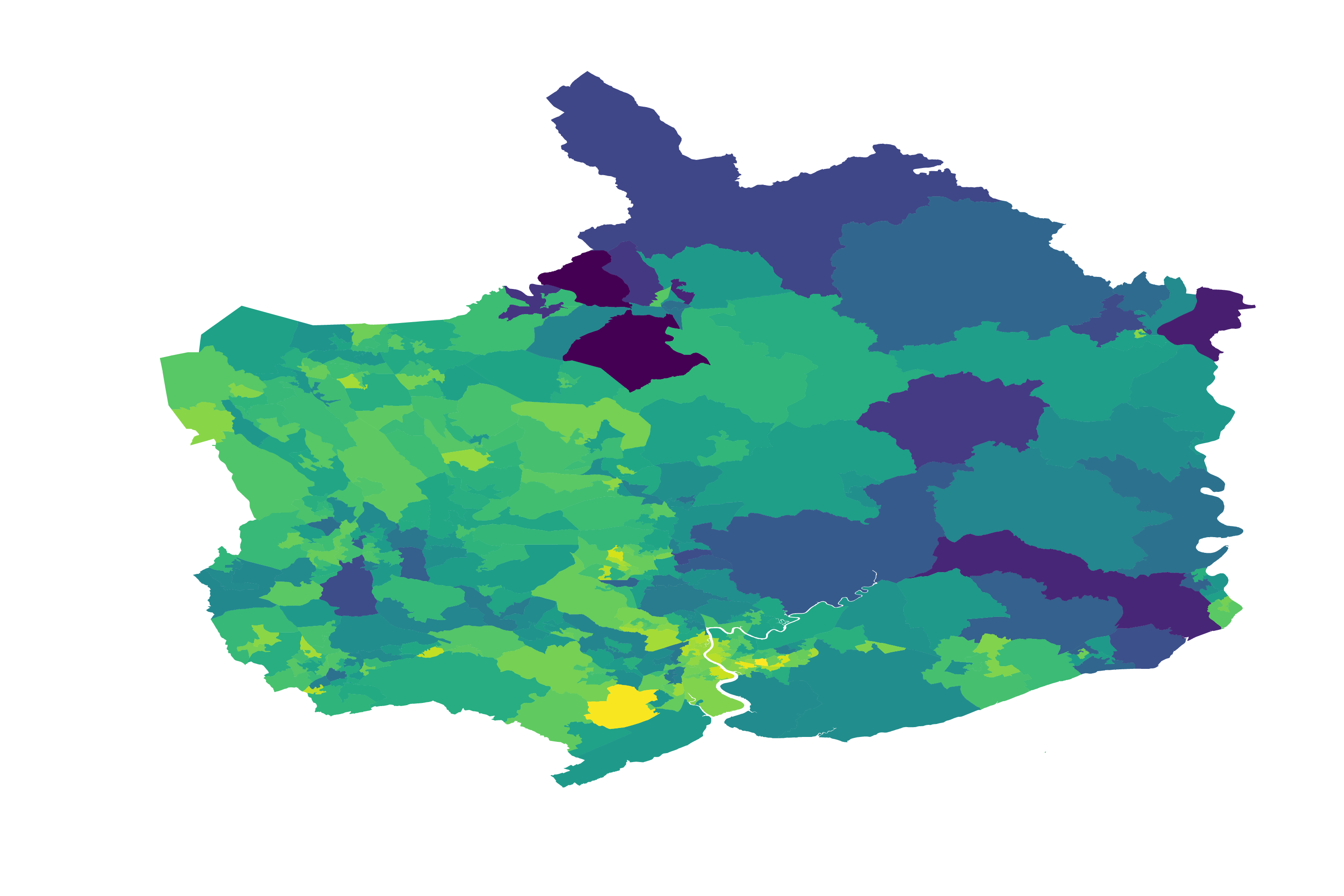

In addition to the polygons, I used two other data sets, containing information on WIMD deprivation measures for each LSOA (Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation, a ranking where 1 denotes the most deprived LSOA, and 1909 denotes the most deprived LSOA), and the population over 60 years of age of each LSOA. I downloaded these from StatsWales and the ONS:

Reading Geojson

It’s easy to read in geojson to geopandas:

import geopandas as gpd

assert geopandas.__version__ == '0.3.0'

world = gpd.read_file('abuhb_world.geojson')world is a GeoFataFrame object, which behaves exactly like a pandas

DataFrame.

After using Pandas to read in the deprivation and population datasets, I

combined the three data frames (using Pandas) such that world contains three

extra columns: WIMD, Over 60 a County:

>>> world

objectid lsoa11cd lsoa11nm lsoa11nmw st_areasha st_lengths geometry WIMD Over 60 County

0 34131 W01001325 Caerphilly 003A Caerffili 003A 1.975810e+06 9595.912399 POLYGON ((-3.222590332332996 51.69544541936416... 219 342 Caerphilly

1 34132 W01001326 Caerphilly 003B Caerffili 003B 1.418504e+06 7206.074574 POLYGON ((-3.218658752736475 51.69265017758838... 190 497 Caerphilly

2 34133 W01001327 Caerphilly 014A Caerffili 014A 1.368584e+07 26141.148134 POLYGON ((-3.133625203219097 51.65362006379572... 1114 451 Caerphilly

3 34134 W01001328 Caerphilly 014B Caerffili 014B 2.343212e+06 10639.884639 POLYGON ((-3.126845962218699 51.66067765558952... 815 370 Caerphilly

4 34135 W01001329 Caerphilly 014C Caerffili 014C 4.799436e+05 4207.033238 POLYGON ((-3.124476654827622 51.63506150073896... 692 365 CaerphillyPlotting a Map

Plotting a map of the polygons is easy:

world.plot()

To designate how the polygons should be coloured, use arguments:

- Designate which column to use as values with

column - Designate the colormap to use with

cmap

You can also integrate with matplotlib’s object-orientated framework:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1)

world.plot(column='Over 60', cmap='viridis_r', ax=ax)

ax.axis('off')

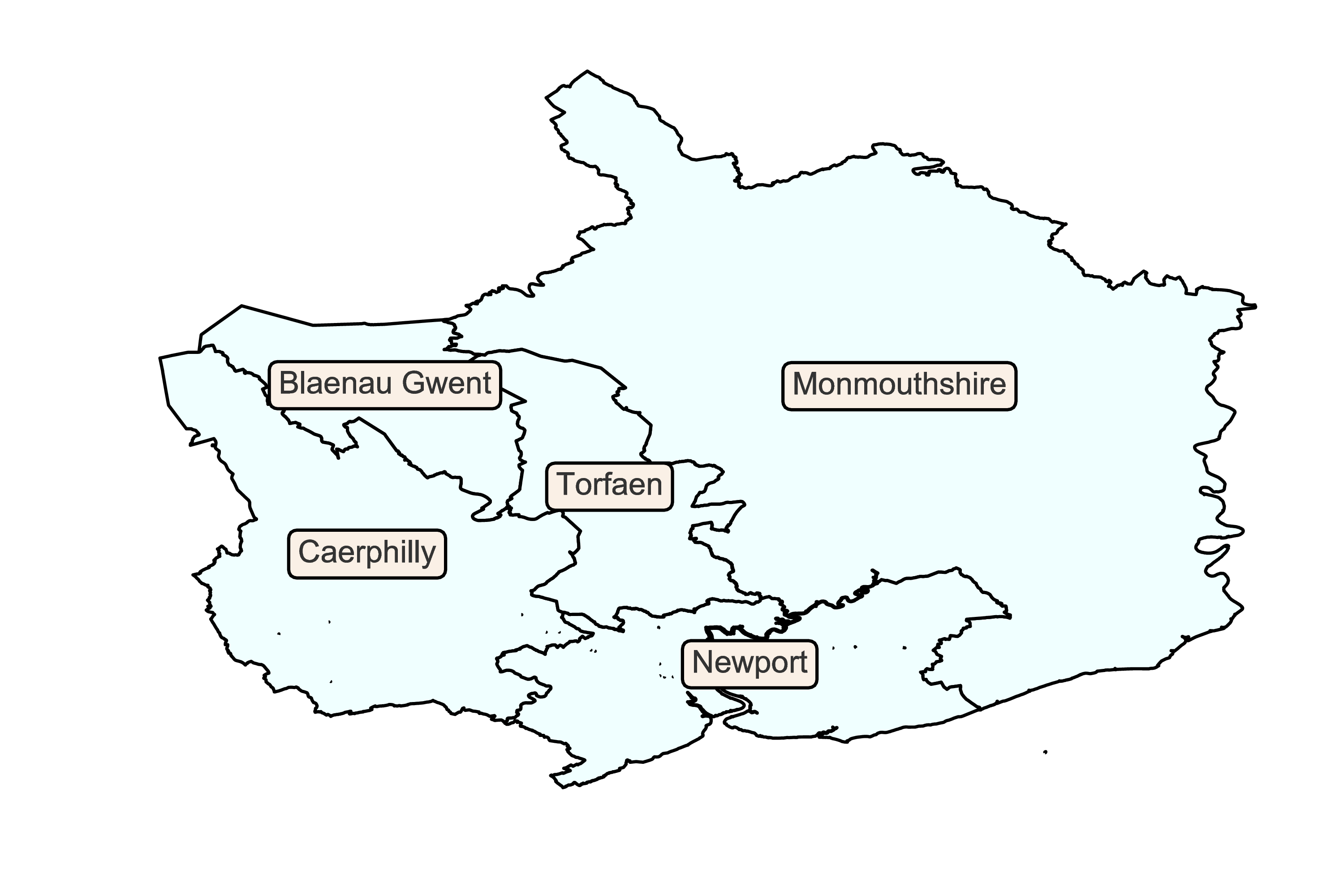

Manipulating Geometry

There are a number of methods for manipulating the geometry of the polygons.

Geopandas’ method of grouping is dissolve, which groups polygons with similar

properties and creates one big polygon from them.

Grouping LSOAs by county:

>>> counties = world.dissolve(by='County')

>>> counties

geometry

Sir

Blaenau Gwent POLYGON ((-3.219457536348314 51.74573457863166...

Caerphilly POLYGON ((-3.123546981902226 51.58721244839312...

Monmouthshire (POLYGON ((-2.781429130096552 51.5252840700888...

Newport (POLYGON ((-2.903851574580124 51.6274883996199...

Torfaen POLYGON ((-2.976496118298735 51.64839999700513...We can find the centre point of a polygon with centroid:

counties['centroid'] = counties['geometry'].centroidOne use of finding a centre point of a polygon is to label polygons:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1)

counties.plot(color='azure', edgecolor='black', ax=ax)

props = dict(boxstyle='round', facecolor='linen', alpha=1)

for point in counties.iterrows():

ax.text(point[1]['centroid'].x,

point[1]['centroid'].y,

point[0],

horizontalalignment='center',

fontsize=10,

bbox=props)

ax.axis('off')

Geopandas also has a number of clever methods for dealing with different map projections

Conclusion

I have enjoyed playing with Geopandas, and a believe that the maps created are very beautiful.

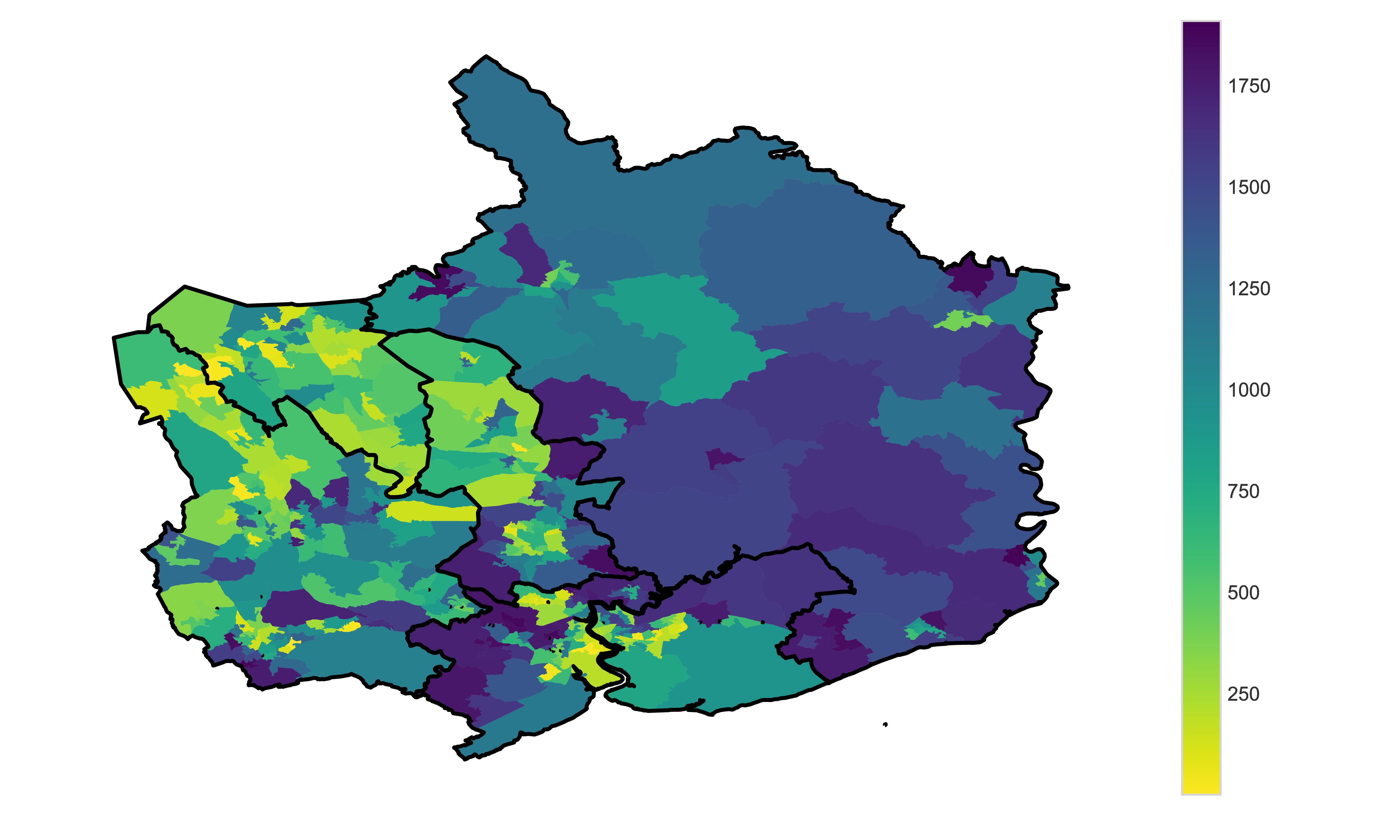

Lastly, I will join two maps, LSOAs and counties, to look at deprivation.

Here I will use the GeoDataFrame counties to add black lines separating the

five counties.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, figsize=(10, 6))

world.plot(column='WIMD', ax=ax, cmap='viridis_r')

counties.plot(color='None', edgecolor='black', linewidth=2, ax=ax)

ax.axis('off')

vmin = world['WIMD'].min()

vmax = world['WIMD'].max()

# Create colorbar

sm = plt.cm.ScalarMappable(cmap='viridis_r', norm=plt.Normalize(vmin=vmin, vmax=vmax))

sm._A = []

cbar = fig.colorbar(sm)

We can see that Monmouthshire has higher deprivation ranks than the other counties. Comparing with the map of population over 60 years of age, we can see that Monmouthshire has more older people than the other counties. In fact, the deprivation pattern and the pattern of population over 60 are awfully similar. Have we discovered something interesting? Are people over 60 more likely to move to areas with less deprivation?

Although the maps look nice, it’s difficult so say with these sort of maps, because geographic information has so many covariates. In this case, WIMD scores are calculated from a number of covariates. One of them is unemployment: retired people do not count as unemployed, so the more older people there are in an area, unemployment will fall. It seems that a number of WIMD’s covariates are affected by older people, therefore we cannot draw any conclusions here.

Despite this, Geopandas is a fantastic tool, it produces very pretty maps, and is easy to use if you are already familiar with Pandas.