Day-tripping to Bletchley

I took a day off work on Monday (yay!) and went day-tripping. I visited Bletchley Park, location of the legendary top-secret British codebreaking operation during the second world war. Here a team of mathematicians, ‘men and women of a professor type’, civil servants, and staff recruited from the Women’s Services deciphered intercepted radio messages from the German, Italian and Japanese militaries. Intelligence gained from these messages saved countless lives, and is thought to have contributed to ending the war early, although their work did not become public until decades after the war.

Some highlights I learned during my time:

- It wasn’t all about Alan Turing! The codebreaking team was huge, and each person contributed massively to the knowledge and methods. They include Gordon Welchman, Bill Tutte, Mavis Batey, Gwen Watkins, Hugh Alexander, Joan Clarke and many more. The museum did a great job showing this.

- ‘Operation Fortitude’ was a huge secret intelligence deception, deliberately leaking fake information to convince the Germans that the D-Day landings would happen at Calais, not Normandy. This was only possible thanks to messages deciphered at Bletchley that gave insight into Hitler’s distrust of his staff, German intelligence operations, and confidence that the Germans had fallen for the plan. Thanks to this the D-Day landings were a success, with Allied soldiers facing far less German soldiers in Normandy as they were all waiting for the landings in Calais.

- You had to be very careful acting on the information gained by deciphered messages: no one was to know about the codebreaking work, so information gained here was disguised as evidence stolen by spies before being handed to senior officials! Sometimes it was even better not to act on this intelligence, to ensure the Germans wouldn’t get suspicious that their codes were being broken.

The museum also gave some insight into the codebreaking process. Here I’ll look at a one particular method that caught my attention, using some Python code available here to implement the cyphers.

Let’s start with an ancient cypher: the Caesar shift cypher:

The Caesar Shift Cypher

This is one of the simplest cyphers. A message is encoded by shifting each letter of the message along the alphabet a fixed number of times. For example the message ‘ALAN TURING’, with key 3 would be encoded by shifting A by 3 to get D, L by 3 to get O, and so on:

>>> import cypher

>>> cypher.caesar('ALANTURING', 3)

'DODQWXULQJ'With the key, deciphering the message is simple, just working backwards shifting each letter backwards by 3:

>>> cypher.caesar('DODQWXULQJ', -3)

'ALANTURING'But if an enciphered message is intercepted without the key, how would we break the cypher? The key here is to realise something about the language the message is written in. In English the letters E, T and A occur most often, and X, J, Q and Z occur least often.

Consider the intercepted message below, which we believe to be in English.

>>> scrambled_message

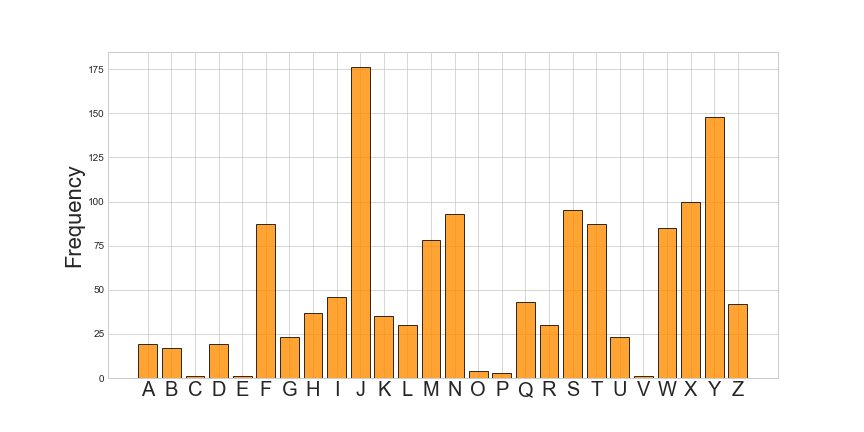

'BJMTQIYMJXJYWZYMXYTGJXJQKJANIJSYYMFYFQQRJSFWJHWJFYJIJVZFQYMFYYMJDFWJJSITBJIGDYMJNWHWJFYTWBNYMHJWYFNSZSFQNJSFGQJWNLMYXYMFYFRTSLYMJXJFWJQNKJQNGJWYDFSIYMJUZWXZNYTKMFUUNSJXXYMFYYTXJHZWJYMJXJWNLMYXLTAJWSRJSYXFWJNSXYNYZYJIFRTSLRJSIJWNANSLYMJNWOZXYUTBJWXKWTRYMJHTSXJSYTKYMJLTAJWSJIYMFYBMJSJAJWFSDKTWRTKLTAJWSRJSYGJHTRJXIJXYWZHYNAJTKYMJXJJSIXNYNXYMJWNLMYTKYMJUJTUQJYTFQYJWTWYTFGTQNXMNYFSIYTNSXYNYZYJSJBLTAJWSRJSYQFDNSLNYXKTZSIFYNTSTSXZHMUWNSHNUQJXFSITWLFSNENSLNYXUTBJWXNSXZHMKTWRFXYTYMJRXMFQQXJJRRTXYQNPJQDYTJKKJHYYMJNWXFKJYDFSIMFUUNSJXXUWZIJSHJNSIJJIBNQQINHYFYJYMFYLTAJWSRJSYXQTSLJXYFGQNXMJIXMTZQISTYGJHMFSLJIKTWQNLMYFSIYWFSXNJSYHFZXJXFSIFHHTWINSLQDFQQJCUJWNJSHJMFYMXMJBSYMFYRFSPNSIFWJRTWJINXUTXJIYTXZKKJWBMNQJJANQXFWJXZKKJWFGQJYMFSYTWNLMYYMJRXJQAJXGDFGTQNXMNSLYMJKTWRXYTBMNHMYMJDFWJFHHZXYTRJIGZYBMJSFQTSLYWFNSTKFGZXJXFSIZXZWUFYNTSXUZWXZNSLNSAFWNFGQDYMJXFRJTGOJHYJANSHJXFIJXNLSYTWJIZHJYMJRZSIJWFGXTQZYJIJXUTYNXRNYNXYMJNWWNLMYNYNXYMJNWIZYDYTYMWTBTKKXZHMLTAJWSRJSYFSIYTUWTANIJSJBLZFWIXKTWYMJNWKZYZWJXJHZWNYDXZHMMFXGJJSYMJUFYNJSYXZKKJWFSHJTKYMJXJHTQTSNJXFSIXZHMNXSTBYMJSJHJXXNYDBMNHMHTSXYWFNSXYMJRYTFQYJWYMJNWKTWRJWXDXYJRXTKLTAJWSRJSYYMJMNXYTWDTKYMJUWJXJSYPNSLTKLWJFYGWNYFNSNXFMNXYTWDTKWJUJFYJINSOZWNJXFSIZXZWUFYNTSXFQQMFANSLNSINWJHYTGOJHYYMJJXYFGQNXMRJSYTKFSFGXTQZYJYDWFSSDTAJWYMJXJXYFYJXYTUWTAJYMNXQJYKFHYXGJXZGRNYYJIYTFHFSINIBTWQI'Then consider the frequency of the letters:

>>> from collections import Counter

>>> freqencies = Counter(scrambled_message)

J occurs most often, so could this be E? That would mean a shift of 5. C, E and V occur least often. Under a shift of 5 that would imply the letters Q, X and Z. So a shift of 5 is plausible:

>>> cypher.caesar(scrambled_message, -5)

'WEHOLDTHESETRUTHSTOBESELFEVIDENTTHATALLMENARECREATEDEQUALTHATTHEYAREENDOWEDBYTHEIRCREATORWITHCERTAINUNALIENABLERIGHTSTHATAMONGTHESEARELIFELIBERTYANDTHEPURSUITOFHAPPINESSTHATTOSECURETHESERIGHTSGOVERNMENTSAREINSTITUTEDAMONGMENDERIVINGTHEIRJUSTPOWERSFROMTHECONSENTOFTHEGOVERNEDTHATWHENEVERANYFORMOFGOVERNMENTBECOMESDESTRUCTIVEOFTHESEENDSITISTHERIGHTOFTHEPEOPLETOALTERORTOABOLISHITANDTOINSTITUTENEWGOVERNMENTLAYINGITSFOUNDATIONONSUCHPRINCIPLESANDORGANIZINGITSPOWERSINSUCHFORMASTOTHEMSHALLSEEMMOSTLIKELYTOEFFECTTHEIRSAFETYANDHAPPINESSPRUDENCEINDEEDWILLDICTATETHATGOVERNMENTSLONGESTABLISHEDSHOULDNOTBECHANGEDFORLIGHTANDTRANSIENTCAUSESANDACCORDINGLYALLEXPERIENCEHATHSHEWNTHATMANKINDAREMOREDISPOSEDTOSUFFERWHILEEVILSARESUFFERABLETHANTORIGHTTHEMSELVESBYABOLISHINGTHEFORMSTOWHICHTHEYAREACCUSTOMEDBUTWHENALONGTRAINOFABUSESANDUSURPATIONSPURSUINGINVARIABLYTHESAMEOBJECTEVINCESADESIGNTOREDUCETHEMUNDERABSOLUTEDESPOTISMITISTHEIRRIGHTITISTHEIRDUTYTOTHROWOFFSUCHGOVERNMENTANDTOPROVIDENEWGUARDSFORTHEIRFUTURESECURITYSUCHHASBEENTHEPATIENTSUFFERANCEOFTHESECOLONIESANDSUCHISNOWTHENECESSITYWHICHCONSTRAINSTHEMTOALTERTHEIRFORMERSYSTEMSOFGOVERNMENTTHEHISTORYOFTHEPRESENTKINGOFGREATBRITAINISAHISTORYOFREPEATEDINJURIESANDUSURPATIONSALLHAVINGINDIRECTOBJECTTHEESTABLISHMENTOFANABSOLUTETYRANNYOVERTHESESTATESTOPROVETHISLETFACTSBESUBMITTEDTOACANDIDWORLD'And we’ve cracked the code, this is the American declaration of independence!

>>> declaration = cypher.caesar(scrambled_message, -5)The Enigma Machine

During the second world war, the Germans used a sophisticated ciphering machine called Enigma, pictured below. First the sender would configure the machine, and then set the staring positions. Then using the keyboard, would type the message, the encrypted message would light up as you typed, allowing a colleague to jot down the encrypted message before sending it via radio in Morse code.

An important feature of the machine was that it was it’s own inverse. Using the same configurations, and same starting positions, you could type in the encrypted message and the original message would light up.

>>> cypher.enigma('ALANTURING', 'BFG')

'CKYCEZCDZB'

>>> cypher.enigma('CKYCEZCDZB', 'BFG')

'ALANTURING'How it worked

The machine contains a switchboard, three rotors, and a reflector.

- The switchboard would cause 10 simple substitutions: e.g. swap A to K and K to A; swap M to U and U to M, and so on.

- Each rotor acted like a Caesar shift cypher on a jumbled up alphabet. This jumbling up of the alphabet was unique to the rotor, of which there was a choice of five, but only three chosen. Furthermore the jumbling up of each rotor could be further customised.

- The reflector paired up letters of the alphabet, and did a swap. This is fundamental in the machine being its own inverse.

So if I was to press the letter Q:

- First it goes through the switchboard, which could swap Q to T.

- It then goes through the \(1^{\text{st}}\) rotor, shifting this T along a jumbled alphabet, to become U.

- It then goes through the \(2^{\text{nd}}\) rotor, shifting this U along a jumbled alphabet, to become M.

- It then goes through the \(3^{\text{rd}}\) rotor, shifting this M along a jumbled alphabet, to become R.

- It then hits the reflector, swapping R to Y.

- It then goes backwards through the \(3^{\text{rd}}\) rotor, shifting this Y to C.

- It then goes backwards through the \(2^{\text{nd}}\) rotor, shifting this C to A.

- It then goes backwards through the \(1^{\text{st}}\) rotor, shifting this A to G.

- Finally it goes through the switchboard again, which could swap G to L.

Then L lights up. Thus Q is mapped to an L.

Easy?

But before you type the next letter, the first rotor rotates by one letter, essentially increasing the shift of that Caesar shift by one. So the next letter would have a different mapping. Every time the first rotor shifts 26 times, the second rotor shifts. And each time the second rotor shifts 26 times, the third rotor shifts. So the first \(26^3 = 17576\) letters are each enciphered with a different mapping.

The starting position of the rotors determine where in the cycle of 17576 mappings the message begins.

Combining the choice and order of the rotors, customisations of these rotors, the switchboard combinations, and the rotor starting positions, there are a possible 156 million million million possible cyphers used to encode any one message. So if an message is intercepted, how did they break the code?

Breaking the code

This was down to human complacency.

Each day all German messages would use the same rotors, rotor order, rotor customisation, and switchboard combination. Once these were determined (using many other clever methods) the only variation in the messages of a single day were the rotor staring positions.

One ingenious method called “Banburismus” exploited the laziness of the message senders. Some senders only changed the rotor starting positions by a small amount between messages. So two different messages by that sender can be compared.

Useful fact:

- Overlaying two different strings of ‘random’ letters, they will coincide with probability \(\frac{1}{26}\).

- Overlaying two different strings of English, they will coincide more often.

It does not matter if the English strings are encrypted! As long as they are encrypted in the same way.

Another useful fact:

- A string encrypted with starting position ‘ATT’, and the same string encrypted with starting position ‘CTT’ are the same, if the second string begins from the third letter (as C is two letters on from A).

>>> cypher.enigma('ALANTURING', 'ATT')

'RCJCXBVLLJ'

>>> cypher.enigma('ANTURING', 'CTT')

'JCXBVLLJ'Banburismus exploited these two facts, checking the probability of coinciding letters of two strings at different shifted intervals. The interval which yielded the greatest probability of coinciding letters is more than likely to be the interval between the starting positions of the rotors of the two messages.

Imagine we intercept a message from a lazy cryptographer, and somehow discover it’s starting position was ‘BLY’:

>>> encrypted_declaration = cypher.enigma(declaration, 'BLY')

>>> encrypted_declaration

'KHCJOAPGJHDYMYXVPFCNJTGIAZYLORJQWXDQNPYPNKPUIFOHEIBACXLREMQSNVOXAJXINLJGYMLUPRADTWNGPTKFIPNEWRJMEFVIQYVWYVCGSSOBPVBEDOMPNUXGFLISPMMTLNKOQPFRMDMMQZIKEYJXLSJOYKUVQCTJOHUPCPLMUSKBOWAHIUCHWZILPIPODHQRUSRVQCBRUALWVSYWNMUTWJHGJJHREBFOJUBSADCOGYSJURQJNTQSERODIVEUTMGCURIOEIWYRAWDSRWCOQGEUQBSOFDFBMBZZECZNDVJDCTFDQDDRXBCZLJKPYUBYIRSSDFGKCVXNBVJSFYEFNKWWLWDAPIAMVSWMVLEKXPVSNCWRFZHDDPCIGYZIDERHXZOQPCLXDDNHIYONAUMSWWPLNKRQHQTJCGNNCBEDPTYVVBZOQCJVXBRXJHKYZBKLGIEBYXQPDIJFNUUZZTKFJDUURUNJVOMQRUFJKGVRRJKORMQQBYEGDKJAQFYZNKCVVUDPFWYJMJJOHPMOTDXIYZWZCQHIYXCQWMAXZEXEFWXPQKRGSDKJPZSRANMTLOSYOUUJLNMQDQSZZUQJAVBOZJBZYJZLJKMNIZLJKMGCTNNRVAJZLWBREMJAEWPKRJPHFRCJZQWCITVTTPURCNYDKHWNQYBLPHBHVJNTICQCAZVCEDLAZEHVRCUTVLRXBYAQWENDXVWOPJINTFWPKLWKDFBWCMFWLYGPKVHAIOEWPARVYLYAWSNKLPCNJJWCIYLVZPSHZKVLTFTZVIDFERWVMUVGGEMLQGXCGMBDTLTTBVTMKICXFZTQURQZVOUMNPQPKETNTXBDEXGERBRUGXUUXAWMOMXEHVORITUSDHNFQPYAQBVFAWJSYYPVZHWAZWVXMEDAOXGOLBNJPZADJQSJBYMHLHZDWUVCBXDLJVHGYSYSUHPJIUDILUTAHDJSJVYCVJAJNWIFOBMBMVHDGZUMJDDAWVSPCOVIOMKFPBSYDUCFGRZEPJQDUHQTHYXJRAZPDPNIPQZJJEGQRTJBDGRFGYRJJSEXDDDOIPPFRUWCXHHJYFORFGFISSKADJKQUBBFQODJKFJKUZDHHFLFKWGOQRZUVYVDSUPOPQXCJBFXQBQZQHCISIAJGQCOFIWEUADFMDOLAJQLRDBWTTKWJGWEAAQJCHLLHTSUJYSTKIZMYFHQZDNDKHTSTBVFQZWZQXJKULQDDGJQTRIOKCYSHSUWCAUCLWAOMUVGGHZMNJIAMCKWCTRJRNFMATDXYQWMIFYTCMSWZUMVWHXPKFGONWZUBOWUHJBAMCXSKTFWBMIOFT'Later that day we intercept another message from the same lazy cryptographer:

>>> scrambled_message

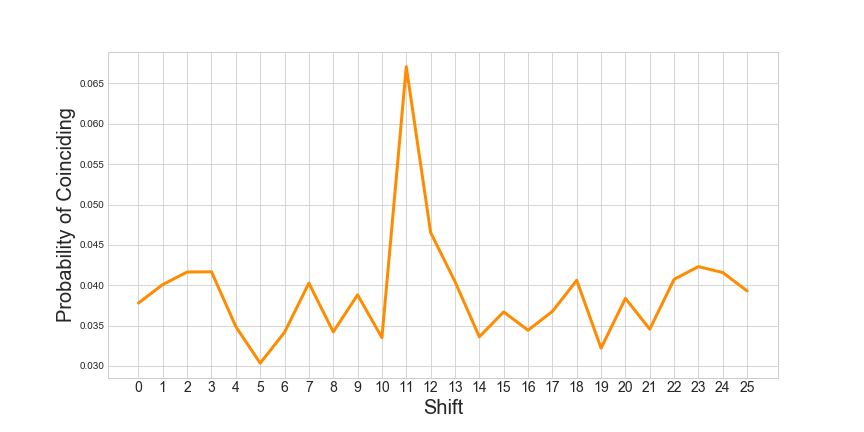

'WHQLPKVQNJDIBDWMHWJVKBWJFMKRAAXPIEAQUDAVCVRBQUMDXKJFFGSMUNKTUVDSRFAXOVWYOXWHEMYVUDRDTMRZPRKOSXJHOBVOADVLCSJZYUUEGISZVDUVLJOWXBTULWVJOWKSEHSJMVSNUTUQCTFAHMSFTVCQOZSDYAFKRZYDDFVVFDCIQWABWWWMCAEIUPLPIRKOIIDMHSRZJCGSIHCSURUBZACFEKBEQCREQBVRWDUDCNYCTYWDJVHBWFNCJWGDHNJPLBMJITSOYYLMFHTBPXRUOESXQQLKFNAFZYBWLBLFPPNVEUSXKRCYKWCGMQSVEGRBJEKQTBWGPPXKNRSHCMKNCGODDKWOBKVZLMAZEBGDHJNDUIWKJBLVWVBXXZUECIYXEJFBBBJLQFGXFUEOMPOTMPAJQDZBTGPCAZQXIOTHKYJJWDOYFTJFWFNYGHEYHRVPLMMSUPJJHCGWMIHDNFXWPPUBYRMNJQVKHZTYVYLJVZIDVBZQDXXWGBJYQJCGHRWSAKDRJJTPGPEZHKYLRTROXIPWUTZMPRKTGALBCHDHKBVTVUPIMNWOQBJCGRRBJKWVNVSCKUMYGBRXJSWTOXVZKWKRSRGNKJTDAPNRSDJMEKRJBHXTITRMUJGOOGMCFCNEJTKSHCJSBUNFCJNALNGUYBURDAJGZKMSFDKQBABJXHBRKTFCVRGPQKAEDJHCEUFXQXYNQYLPTSZEJZHCKVHBDYEZLPGHYATRSNJCDIRBOUXYQWZGSBNSVZCIAYIWBDBNXBEYEYEMMLOAUGHFGIYPIDRVPKBMXXHMHCBFYHYZPEOOBDROQKUZNMIYITELSFGWXZCMKYURZXSNOCCMMCAHFGMMECLPSZDSJFWLVIHKESTEONHYFKOXSBXGCXGAPHGAVJXAHBXKWWQBQQRQGNJVXXIMTJBKHMGBNEBJNMOWGLWNECVGPMHVVKJTIVGSHBSFQLDEHWXNQSVBHJIDYNKCYUZVQPMANTKOHNOCMXCOWKJNARDKVEIXZECCJVEXXDHTHYHZUPFZZJQMTJOYPBPNVUGUCNKHGIDYEVRDQARXKGAXEJVGFSQZIVJVABAPZALTMVGRVMNUPFLQBKAZSXJFUICWSUDUWUDZVUKRGACIXQVCJBHNHKBHODVGOFYUKKJUXOZBWVGURPAEAQLCBDOEEJIVVUWEPUANUCGSEGGMJMKNYODVZDDFSRDMOLFKSSYGWOEXRXDHZOALEVJIXEGMDYYSCGMUUTLXAQREZZZZYWPZZRJAVPWPBXLGPQKFDEEJSKNWSAGUAKEYBIRKKAYEMSOKMJRXRTAXSOYDXGQJQXUNGDQKOYRSKUTHZLXRBEXOSNMZDQJXWTNXYXBCQTOGXZHAVBBGGCPCAMSKOXCFQTPRWCUDMQORRVABBISD'We do not know the starting positions of the rotor to be able to decipher this message, but we do know the cryptographer was lazy, so it wouldn’t be that far away from ‘BLY’. Now we employ Banburismus to find the proportion of coinciding letters for each shift:

>>> def banburismus(l1, l2, shift):

... coincides = [a == b for a, b in zip(l1[shift:], l2)]

... return sum(coincides) / len(coincides)

>>> banburismus(encrypted_declaration, scrambled_message, 1)

0.040090771558245086This is checked for a number of shifts:

A shift of 11 produces the largest proportion of coinciding letters, so this is a good guess. ‘BLY’ shifted by 11 would be ‘MLY’, thus:

>>> cypher.enigma(scrambled_message, 'MLY')

'ALLHUMANBEINGSAREBORNFREEANDEQUALINDIGNITYANDRIGHTSTHEYAREENDOWEDWITHREASONANDCONSCIENCEANDSHOULDACTTOWARDSONEANOTHERINASPIRITOFBROTHERHOODEVERYONEISENTITLEDTOALLTHERIGHTSANDFREEDOMSSETFORTHINTHISDECLARATIONWITHOUTDISTINCTIONOFANYKINDSUCHASRACECOLOURSEXLANGUAGERELIGIONPOLITICALOROTHEROPINIONNATIONALORSOCIALORIGINPROPERTYBIRTHOROTHERSTATUSFURTHERMORENODISTINCTIONSHALLBEMADEONTHEBASISOFTHEPOLITICALJURISDICTIONALORINTERNATIONALSTATUSOFTHECOUNTRYORTERRITORYTOWHICHAPERSONBELONGSWHETHERITBEINDEPENDENTTRUSTNONSELFGOVERNINGORUNDERANYOTHERLIMITATIONOFSOVEREIGNTYEVERYONEHASTHERIGHTTOLIFELIBERTYANDSECURITYOFPERSONNOONESHALLBEHELDINSLAVERYORSERVITUDESLAVERYANDTHESLAVETRADESHALLBEPROHIBITEDINALLTHEIRFORMSNOONESHALLBESUBJECTEDTOTORTUREORTOCRUELINHUMANORDEGRADINGTREATMENTORPUNISHMENTEVERYONEHASTHERIGHTTORECOGNITIONEVERYWHEREASAPERSONBEFORETHELAWALLAREEQUALBEFORETHELAWANDAREENTITLEDWITHOUTANYDISCRIMINATIONTOEQUALPROTECTIONOFTHELAWALLAREENTITLEDTOEQUALPROTECTIONAGAINSTANYDISCRIMINATIONINVIOLATIONOFTHISDECLARATIONANDAGAINSTANYINCITEMENTTOSUCHDISCRIMINATIONEVERYONEHASTHERIGHTTOANEFFECTIVEREMEDYBYTHECOMPETENTNATIONALTRIBUNALSFORACTSVIOLATINGTHEFUNDAMENTALRIGHTSGRANTEDHIMBYTHECONSTITUTIONORBYLAWNOONESHALLBESUBJECTEDTOARBITRARYARRESTDETENTIONOREXILEEVERYONEISENTITLEDINFULLEQUALITYTOAFAIRANDPUBLICHEARINGBYANINDEPENDENTANDIMPARTIALTRIBUNALINTHEDETERMINATIONOFHISRIGHTSANDOBLIGATIONSANDOFANYCRIMINALCHARGEAGAINSTHIM'And we’ve cracked the code, this is the universal declaration of human rights!

A drawback to this method was the need to have long messages, and the need for a previously cracked message from the same day. A number of other methods were developed at Bletchley including Cribbing, which involved guessing that messages began with common words like ‘weather’, and eliminating many possible starting combinations due to the fact that Enigma could never map a letter to itself. All this cumulated in the construction of the Bombe machine to automate a number of these tasks quickly, although how this machine worked was not explained well at the museum.

Overall I has a great day out combining my interests in history and maths, and became inspired (and a little patriotic) by the work that went on here. We then finished out day by listening to the Maths at the Movies podcast discussing The Imitation Game.