How to Become the most Unpopular President

We all know that first-past-the-post voting is broken. In America you can win the popular vote but lose the presidency. With only 45 days until the US presidential election, what’s the smallest percentage of votes needed to become president?

UK General Elections

The situation in the UK is simpler, so let’s consider UK general elections first. The country is split into 650 constituencies with roughly equal populations. Each constituency votes for an MP, usually associated with a political party, who gain a seat in the House of Commons. The party with over half the seats have a majority and are able to form a majority government. However, each constituency doesn’t elect an MP by majority, they elect by plurality. The candidate doesn’t need a majority of votes to gain a seat, they simply need more votes than any other candidate.

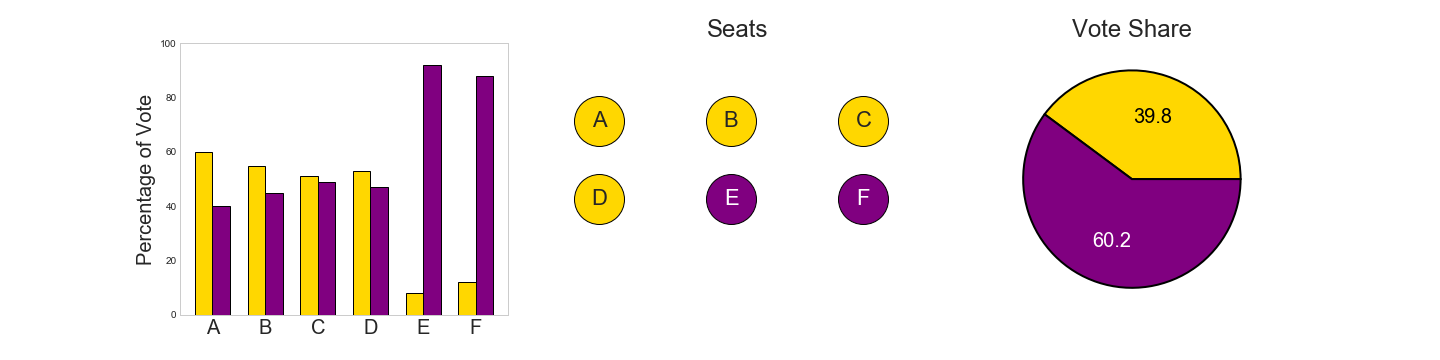

This leads to possible situations in which the party that gains the most votes overall are not able to form a government. For example:

Here there are six constituencies, the yellow party gains 4, and so can form a government. However the purple party won 60.2% of the vote.

So - what’s the minimum percentage of votes can a party gain and still form a majority government?

Let’s begin by finding a strategy using PuLP. For this, let’s assume there are eight constituencies, all constituencies have equal populations, voter turnout is equal in all constituencies, and only two parties put candidates up for election. Let \(C\) be the set of constituencies indexed by \(i\), let \(v_i\) be the number of votes cast for the yellow party in constituency \(i\), and let \(s_i\) the a binary variable indicating whether the yellow party won a seat in constituency \(i\). Now we’ll minimise the proportion of votes cast for the yellow party while ensuring they can form a majority government:

\[\text{Minimise: } \sum_i \frac{v_i}{|C|}\]Subject to:

\[v_i \geq 0 \quad \forall \; i \in C\] \[v_i \leq 1 \quad \forall \; i \in C\] \[s_i \leq v_i + \frac{1}{2} \quad \forall \; i \in C\] \[\sum_i s_i \geq \frac{|C|}{2} + 1 \quad \text{if } c \text{ is even}\] \[\sum_i s_i \geq \frac{|C|}{2} \quad \text{if } c \text{ is odd}\]import pulp

number_of_constituencies = 8

prob = pulp.LpProblem("WorstElection", pulp.LpMinimize)

votes = pulp.LpVariable.dicts("v", range(number_of_constituencies))

seats = pulp.LpVariable.dicts("s", range(number_of_constituencies), cat=pulp.LpBinary)

for constituency in range(number_of_constituencies):

prob += votes[constituency] >= 0.0

prob += votes[constituency] <= 1.0

prob += seats[constituency] <= votes[constituency] + 0.5

if number_of_constituencies % 2 == 0:

prob += sum([seats[s] for s in range(number_of_constituencies)]) >= (number_of_constituencies / 2) + 1

else:

prob += sum([seats[s] for s in range(number_of_constituencies)]) >= (number_of_constituencies / 2)

objective_function = sum([votes[v] for v in range(number_of_constituencies)]) / number_of_constituencies

prob += objective_function

prob.solve()This yields the following strategy:

| Constituency | Vote Share | Seat |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 50% (plus one vote) | 1 |

| 1 | 50% (plus one vote) | 1 |

| 2 | 50% (plus one vote) | 1 |

| 3 | 50% (plus one vote) | 1 |

| 4 | 50% (plus one vote) | 1 |

| 5 | 0% | 0 |

| 6 | 0% | 0 |

| 7 | 0% | 0 |

So we have a strategy - win just 50% (plus one vote) in just over half the constituencies. Here the yellow party forms a majority government with just 31.25% of the vote - while the purple party cannot form a government despite 68.75% of the country voting for them!

Using this strategy for \(n\) constituencies, the share of the vote, \(m(n)\) will be:

\[m(n) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{2n} & \text{if } n \text{ is even}\\ \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{4n} & \text{if } n \text{ is odd.} \end{cases}\]As \(n\) gets larger and larger, this approaches 25% of the vote. Therefore, in the UK with 650 constituencies, with a two-party system, a party can win only 25.08% of the vote and still form a majority government - while a party can gain 74.92% of the vote and be unable to form a government!

More parties?

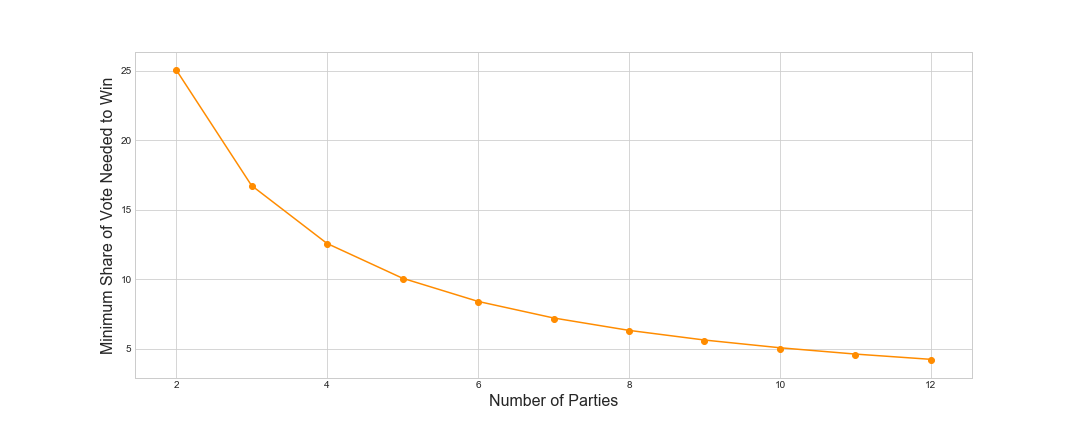

What if there are more parties? Using the same strategy, if there are \(p\) parties, then the least votes needed to win a seat is \(\frac{1}{p}\) plus one vote, with the rest equally shared amongst all other parties. For \(n\) constituencies and \(p\) parties, the smallest share of votes \(m(n, p)\) would be:

\[m(n, p) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{2p} + \frac{1}{2n} & \text{if } n \text{ is even}\\ \frac{1}{2p} + \frac{1}{4n} & \text{if } n \text{ is odd.} \end{cases}\]For 650 constituencies we can see the effect of adding more parties:

If there are 10 parties, then it’s possible to form a majority government with only 5% of the vote!

The Electoral College

In presidential elections in the USA they use a very similar system called the Electoral College. We can consider this a set of constituencies with unequal populations and unequal weightings. Each state, plus the District of Columbia, has a certain amount of ‘electors’, proportional to the population they represent. Voters in California for instance choose 55 electors, while New Mexico chooses 5. Within each state it’s all or nothing: assuming no 3rd party candidate, if one candidate gains at least 50% plus one vote in California, they gain all 55 electors1. The candidate with more than half the electors becomes president.

So what’s the minimum number of votes needed to win the presidency? We only need a small adaptation to the above PuLP code to account fo unequal populations and unequal weightings, and we can find the strategy to minimise the number of votes needed to become president.

# https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/02/14/2020-03000/estimates-of-the-voting-age-population-for-2019

electors = [9, 3, 11, 6, 55, 9, 7, 3, 3, 29, 16, 4, 4, 20, 11, 6, 6, 8, 8, 4, 10, 11, 16, 10, 6, 10, 3, 5, 6, 4, 14, 5, 29, 15, 3, 18, 7, 7, 20, 4, 9, 3, 11, 38, 6, 3, 13, 12, 5, 10, 3]

potential_votes = [3814879, 551562, 5638481, 2317649, 30617582, 4499217, 2837847, 770192, 577581, 17247808, 8113542, 1116004, 1338864, 9853946, 5164245, 2428229, 2213064, 3464802, 3561164, 1095370, 4710993, 5539703, 7842924, 4336475, 2277566, 4766843, 840190, 1458334, 2387517, 1104458, 6943612, 1620991, 15425262, 8187369, 581891, 9111081, 3004733, 3351175, 10167376, 854866, 4037531, 667558, 5319123, 21596071, 2274774, 509984, 6674671, 5951832, 1432580, 4555837, 445025]

prob = pulp.LpProblem("WorstElection", pulp.LpMinimize)

votes = pulp.LpVariable.dicts("v", range(51))

won_states = pulp.LpVariable.dicts("s", range(51), cat=pulp.LpBinary)

for state in range(51):

prob += votes[state] >= 0.0

prob += votes[state] <= potential_votes[state]

prob += won_states[state] <= (votes[state] * (1 / potential_votes[state])) + 0.5

prob += sum([won_states[s] * electors[s] for s in range(51)]) >= (sum(electors) / 2) + 1

objective_function = sum([votes[v] for v in range(51)]) / sum(potential_votes)

prob += objective_function

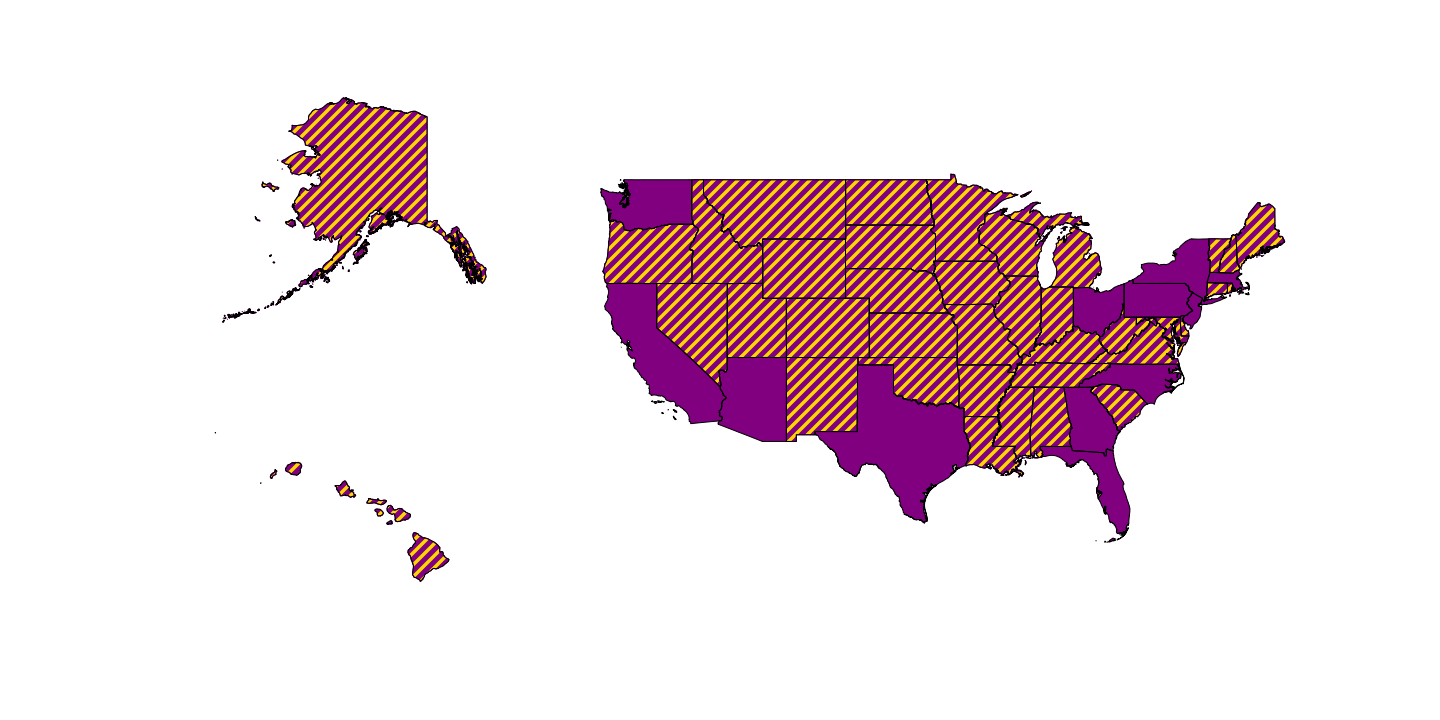

prob.solve()This gives just 21.68% of the vote!

That means a candidate can lose by winning 78.32% of the voters! To put that into perspective, only one president ever, James Monroe in 1820, has ever won an election with a larger percentage of votes!

How can this be? With a similar strategy to the UK one above: gain 50% plus one vote in all states except Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Washington, where you win no votes at all, as in the map below (yellow wins and purple loses).

However, different to UK general elections, in presidential elections it’s all or nothing. The losing 78.32% of voters do not get a voice in the White House! Those votes do not, as in the UK, contribute somewhat towards seats in parliament, there are separate congressional and senate elections for that, with different counting mechanisms.

Now in reality targeting and relying on a specific minimal set of states is impractical because each state has a diverse population. But if we could map minority and special interest groups to state populations, we could easily find a strategy to win an election which targets the least number of homogeneous groups, or requires the least amount of political compromises. Though I don’t think any of what I’ve written is ethical, it is interesting.

-

Except for Nebraska and Maine where only half their electors work like this. However this does not affect the analysis here. ↩