Extrapolating demand across geographies

Our latest paper was recently published online: “Modelling changes in healthcare demand through geographic data extrapolation”, with Paul Harper, Vincent Knight, and Cathy Brooks in Health Systems. Unfortunately, the paper is behind a paywall, so here’s a little TL;DR.

This work was part of my PhD, where I worked with Aneurin Bevan University Health Board in Gwent, South East Wales, to try and model the effect a new healthcare intervention was having on the healthcare needs of a population, in particular the demand at various healthcare facilities. The intervention was called Stay Well Plans (SWPs), and were offered to a subset of the population of people over 60 years of age. So ideally, we’d select a truly random subset of the population to be offered SWPs, record healthcare activity before plans were offered, and then after plans were offered, and compare. We’d use the before and after data to parametrise a demand model, run the model, compare results.

However, this evaluation work began after the scheme began. So we were not collecting all the relevant data to be able to do that. Importantly, the trial plans were only offered to a subset of the population of Newport county, but we wanted to evaluate their effect of demand across the whole of Gwent, which includes Newport and four other counties. So our task was to extrapolate model parameters for the other counties of Gwent, from the Newport parameters. We did this by adjusting for what we believed were three fundamental differences in their geographies and demographics.

The Model

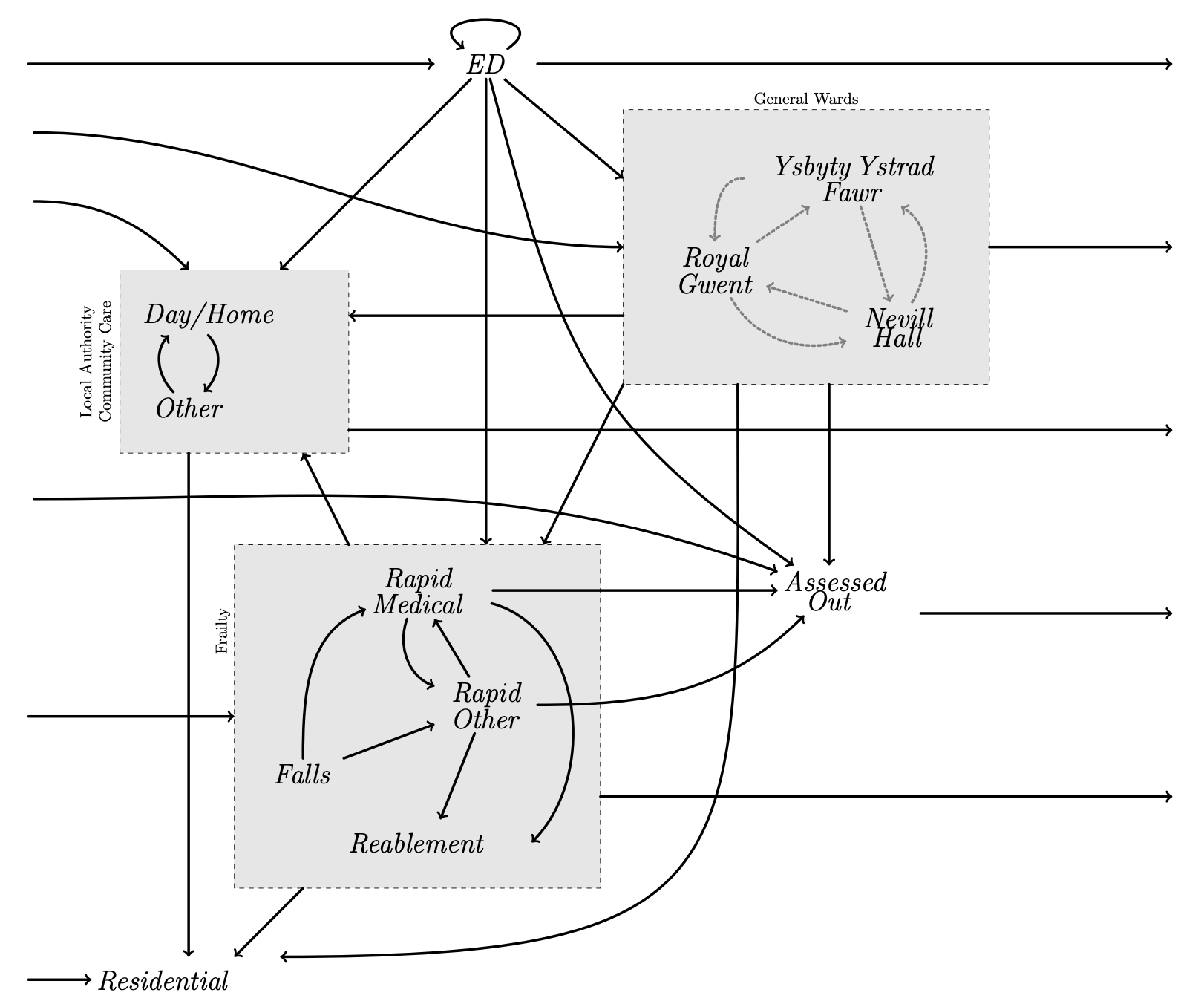

A whole system patient flow model was built, incorporating emergency, secondary, community, and residential care, shown below.

This is modelled as a Markov model, parametrised by different arrival rates, service rates, and transition probabilities for people in each different county. Furthermore, within each county we can identify three types of individuals: those not offered a SWP (because they were well enough not to need one), those offered a SWP and accepted it, and those offered a SWP and rejecting it. Each of these will have their own parameter set too.

But we only have the parameters for Newport. What do we do?

The Methodology

We identified three important differences between the counties that we believed might affect demand: population sizes (the higher the population, the higher the demand); deprivation levels (it is believed that the more deprived an area, the less likely the residents are to accept a SWP); and distances to hospitals (people are more likely to go to their closest hospital).

-

Population sizes:

This is fairly simple: for each county, we multiply the demand by \(\frac{N_c}{N}\), where \(N_c\) is the population of the county, and \(N\) is the population of the original study cohort.

-

Deprivation levels:

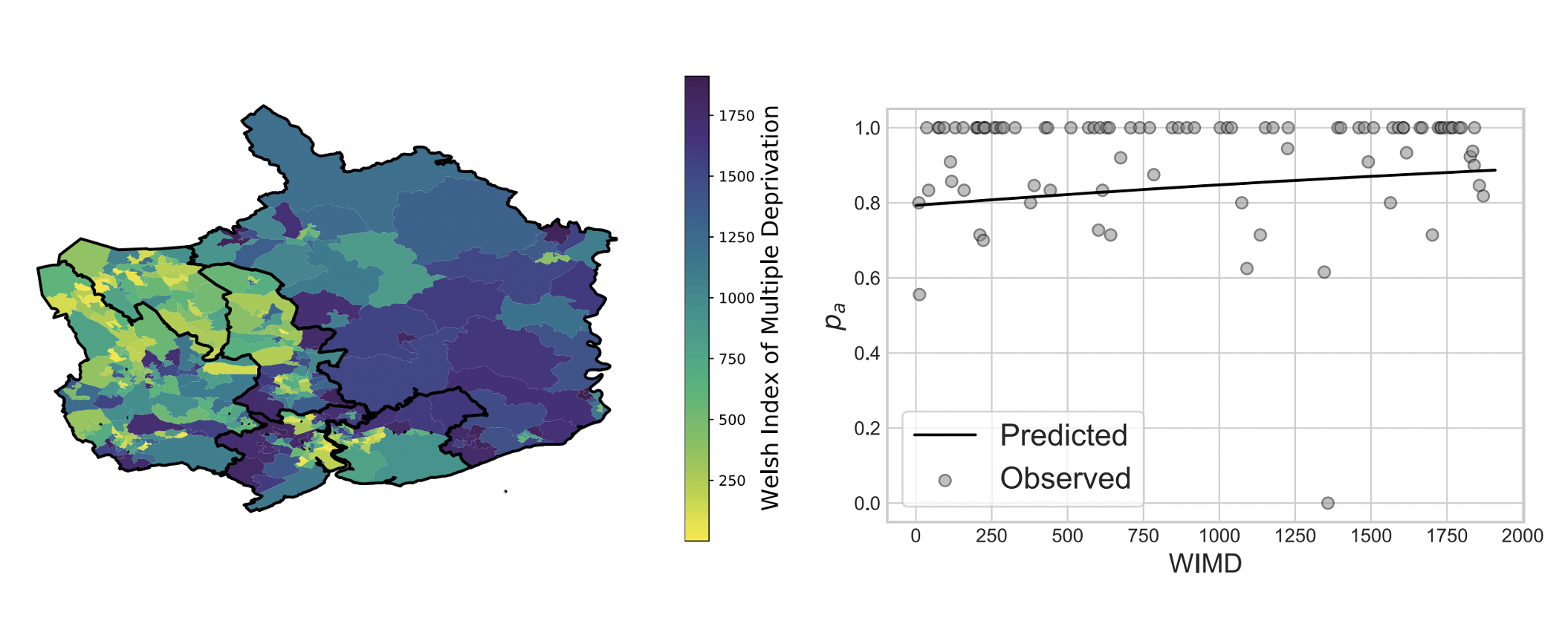

We looked at the relationship between deprivation levels (using the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation, which ranks each Lower Super Output Area in Wales) and SWP uptake within the study cohort. We were very lucky here, Gwent is an extremely diverse region in terms of deprivation, including both the most and least deprived areas in Wales, with a big divide between the affluent rural areas and the less affluent post-industrial valley areas. Luckily, the county of Newport, from which our study cohort came, is just as diverse. We built a logistic regression model to describe and predict uptake from deprivation.

Though the relationship does not look strong, it is statistically significant, and importantly coincides with the expert opinion at the health board. Therefore, we use the logistic regression within each LSOA to predict the number of people accepting or rejecting a SWP, and aggregate across counties. The demand can then be adjusted accordingly.

-

Distances to hospitals:

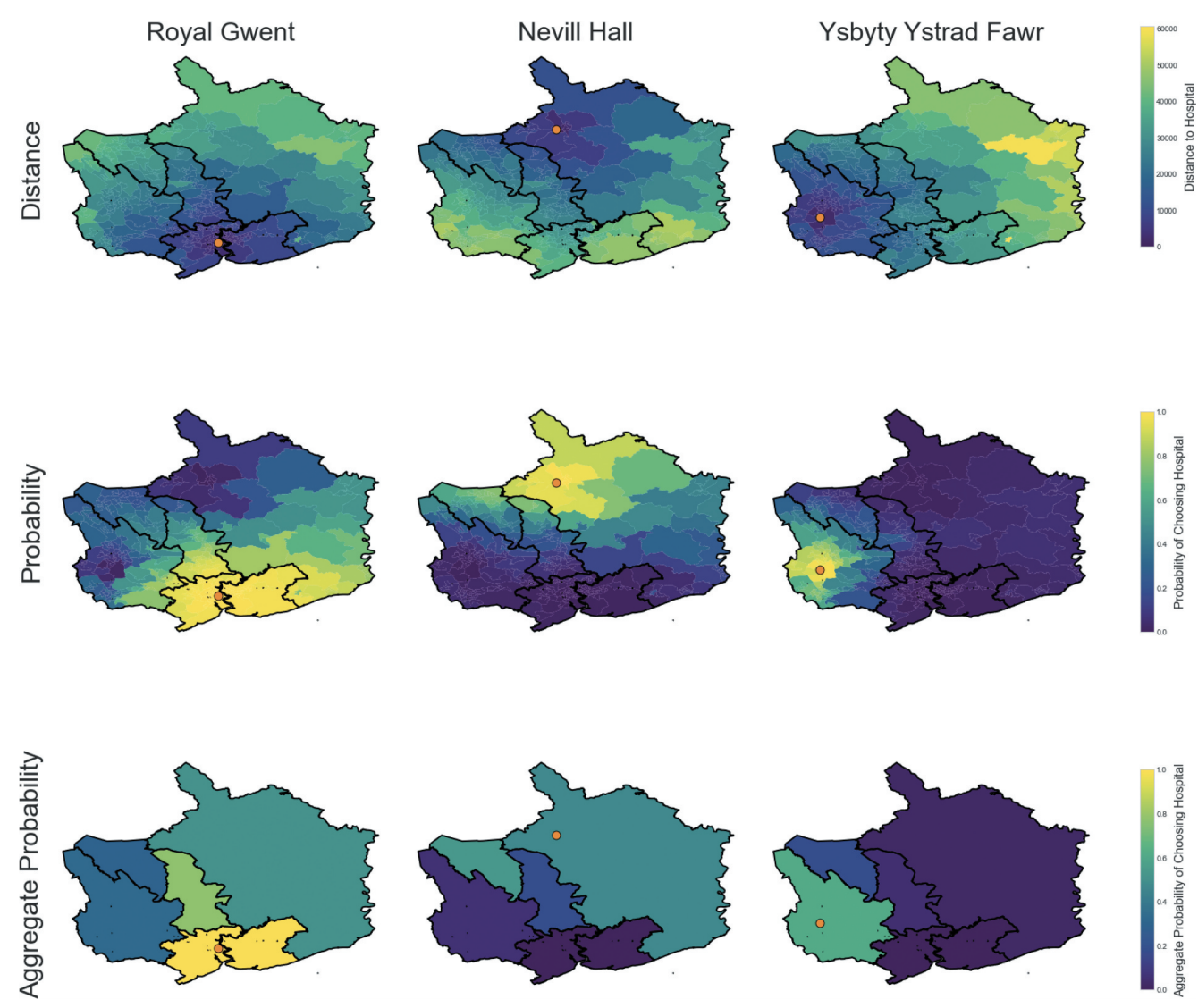

Now we needed to look at distances to each of the three hospitals considered in this model: Royal Gwent in the city of Newport, Nevill Hall hospital in Abergavenny, and Ysbyty Ystrad Fawr in Ystrad Mynach. We’ll assume that the probability of attending each hospital is kindof inversely proportional to their relative distance from your home. More precisely:

\[a_{gl} = \frac{w_g d_{gl}^{-n}}{\sum_j w_j d_{jl^n}}\]where \(a_{gl}\) is the proportion of people from LSOA \(l\) who go to hospital \(g\); \(w_g\) is the size of hospital \(g\), \(d_{gl}\) is the distance from LSOA \(l\) to hospital \(g\), and the sum is over the three hospitals. \(n\) is a hyperparameter that can be tuned to fit the model to the study cohort data. Once we have these for each LSOA, we can aggregate over their populations to get relative probabilities of going to each hospital from each county:

Now, remember all base demands and transition probabilities are from the study cohort, that is Newport. So for each of the other counties, we divide these by the derived Newport probabilities, and multiply by the new probabilities for that particular county. This has the effect of shifting the demand to other hospitals in proportion to the relative distances to the populations they serve.

The full parametrised model is given in the paper. We then use aggregated Markov models to find the effective demand at each healthcare facility. In order to capture some information on variability, a Monte Carlo simulation is also run, assuming Poisson arrivals.

The Results

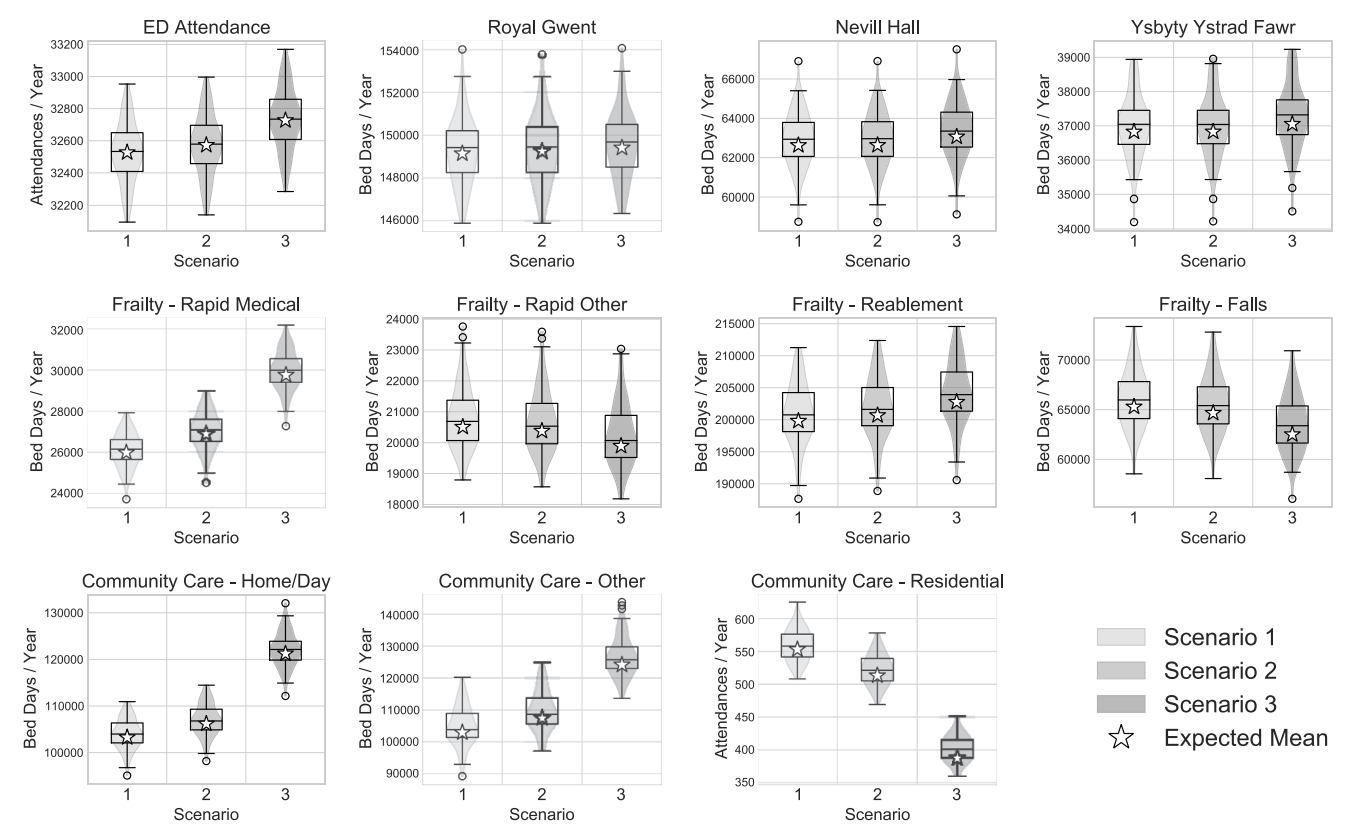

The models are used to run three scenarios, by adjusting the proportion of the population who are offered SWPs in each county:

- What if there were no SWPs offered? (the past)

- What if they were only offered in Newport? (the present)

- What if they were offered in all counties of Gwent? (the future)

The results of the Markov model (stars) and Monte Carlo simulations (box and violin plots) is shown below:

This mainly showed that offering SWPs could result in a re-distribution of demand amongst the frailty services; a large increase in demand at community care services; and a large reduction in demand in residential care. This was favourable, as it indicated that the SWPs were doing their job, that is offering patients care in the community and keeping them in their own homes for longer.

In the paper we also offer further modelling, considering future changing demographics, and a closer look at residential care demand. The work is also discussed in my PhD thesis, where I used these results to consider workforce implications.