Welsh Word Embeddings

Over the last two years I have enjoyed being a part of two Welsh Government funded projects in collaboration with colleagues from the School of Computer Science and the School of English (Irena Spasic, Padraig Corcoran, Dawn Knight, Luis Espinosa Anke, Vigneshwaran Muralidaran, Maxim Filimonov, and Laura Arman). These projects, part of the Welsh Government’s Welsh Language Technology Action Plan, were to train word embeddings of the Welsh language, and cross-lingual word embeddings of the combined Welsh and English lexical space. The projects resulted in two peer reviewed publications and an ebook chapter:

- 2021: Creating Welsh Language Word Embeddings.

Corcoran P, Palmer GI, Arman L, Knight D, & Spasić I. Applied Sciences 11(15), 6896. - 2021: English–Welsh Cross-Lingual Embeddings.

Espinosa-Anke L, Palmer GI, Corcoran P, Filimonov M, Spasić I, & Knight D. Applied Sciences 11(14), 6541. - 2021: A Closer Look at Welsh Word Embeddings. (cy)

Palmer GI, Corcoran P, Arman L, Knight D, & Spasić I. Language and Technology in Wales: Volume I.

The last of these was originally written in Welsh, using automatic translation technology in order to collaborate with people who don’t speak Welsh, which was quite cool. In addition to these, the following resources were produced:

- Welsh language video tutorials on the work,

- Open source Welsh language word embeddings & evaluation datasets,

- Open source English-Welsh cross-lingual word embeddings with training code and sentiment analysis tool.

This was a subject area I hadn’t worked in before, and wanted to write a little TL;DR introducing the work.

Word embeddings?

Word embeddings are vector representations of words. They are a mapping between every word in a language and \(\mathbb{R}^n\), the set of \(n\)-dimensional vectors of real numbers. Therefore, for example, the word “elephant” could be mapped the the vector:

\[\mathbf{v}_{\text{elephant}} = \{0.75, 3.43, -1.22, 1.91, -0.44, -5.72\}\]These can be useful as we can quantify or describe semantic relationships in the language of vectors. Therefore, in a ‘good’ set of word embeddings we want the relationships between the vectors to reflect the corresponding relationships between the words. In order to capture enough information for this, \(n\) is usually chosen to be between 100 and 500. If these relationships are captured, then we should be able observe:

-

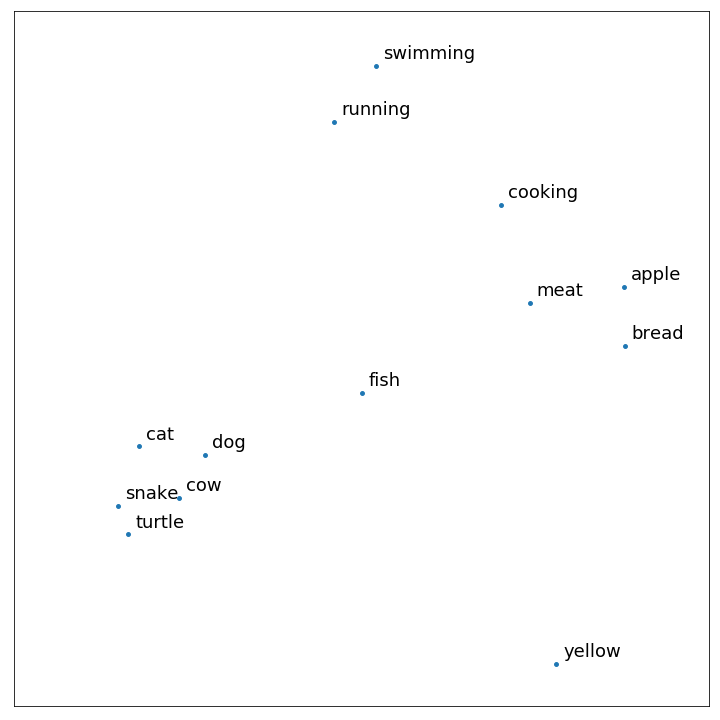

vectors of closely related words should themselves be closely located, e.g. in simplified two-dimensions:

-

and sizes and directions between vectors should be equal if the semantic meaning between their words are equal, e.g. \(\mathbf{v}_{\text{son}} - \mathbf{v}_{\text{daughter}} = \mathbf{v}_{\text{actor}} - \mathbf{v}_{\text{actress}}\). We can see that through rearranging these embeddings have power to predict unknown or unseen words from context.

How?

Any mapping between words and unique vectors are word embeddings. But good word embeddings, those that exhibit these desirable properties, can be found by training on a large corpus of text. A corpus is a lot of sentences, that is words in their context. There are a number of algorithms available to do this, and they rely on the theory of distributional semantics, which states that words appearing in similar contexts have similar meanings.

We considered two algorithms, Skip-gram and CBOW. In general they sweep through the corpus looking at each word in turn, and it’s context window, that is it’s nearest \(k\) words in that sentence. They then attempt to find vectors for each word that maximise the log-likelihood of finding that word in that context window (or, depending on the algorithm, the log-likelihood of finding that context window around that word), where the probability is defined by the the SoftMax distance between the vector of the word and the vectors of the words in the context window.

Other variations that we considered included treating partial or sub-words separately, useful in highly morphological languages. These algorithms are available in the open source Python library gensim.

However, the main source of quality of word embeddings, especially in low-resource languages such as Welsh, is the size and quality of the training corpus. I talk about this, and how we can all help out, in another blog post. We assembled a corpus of 92,963,671 words, collecting from a number of smaller corpora including Welsh Wicipedia, proceedings of the national assembly, BBC news sites, various social media posts, CorCenCC, the Bible, Gwerddon, and more blogs, magazines and academic texts.

After training this corpus on a number of sets of algorithm hyper-parameters, we chose the best performing word embeddings, and they are available here: https://datainnovation.cardiff.ac.uk/is/wecy/access.html.

Any good?

Once downloaded the word embeddings can be loaded with:

import gensim

from gensim.models.callbacks import CallbackAny2Vec

class EpochLogger(CallbackAny2Vec):

'''Callback to log information about training'''

def __init__(self):

self.epoch = 0

def on_epoch_begin(self, model):

print("Epoch #{} start".format(self.epoch))

def on_epoch_end(self, model):

print("Epoch #{} end".format(self.epoch))

self.epoch += 1

model = gensim.models.FastText.load('FastText_WNLT_SkipGram/skipgram_subword_model.model')Now we have loaded the model, we can check out the word embeddings. What’s the vector associated with the word “nofio” (swimming)?

>>> model.wv['nofio']This gives a long array of numbers, not super readable. We can find the 10 closest vectors to this, and their associated words. The standard measure of ‘closeness’ between vectors in this context is the cosine similarity:

>>> model.wv.most_similar(positive=['nofio'], topn=10)

[('nofiol', 0.6012746095657349),

('nofiodd', 0.5929412841796875),

('nofi', 0.5893375277519226),

('pwll', 0.5836290717124939),

('swimsuit', 0.5183103084564209),

('heicio', 0.5182317495346069),

('canwio', 0.5022277235984802),

('rhwyfo', 0.4894988536834717),

('caiacio', 0.4887942969799042),

('phlymio', 0.48672929406166077)]Here we see similar words: some misspellings, nofiodd (swam), pwll (pool), swimsuit in English, heicio (hiking), canwio (canoeing), rhwyfo (rowing), caiacio (kayaking), and phlymio (diving).

How about predicting new words? Above we noted that we could predict the vector for “actress” by rearranging the equation stating the equality of vector differences: \(\mathbf{v}_{\text{actress}} = \mathbf{v}_{\text{actor}} - \mathbf{v}_{\text{son}} + \mathbf{v}_{\text{daughter}}\):

>>> actor, son, daughter = model.wv['actor'], model.wv['mab'], model.wv['merch']

>>> predicted_actress = actor - son + daughter

>>> model.wv.most_similar(positive=[predicted_actress], topn=10)

[('actor', 0.7876081466674805),

('actores', 0.7131889462471008),

('actorion', 0.5787793397903442),

('berfformwraig', 0.5728527307510376),

('comediwraig', 0.5709209442138672),

('digrifwraig', 0.5636816024780273),

('sgriptwraig', 0.5622066259384155),

('athletwraig', 0.5469273328781128),

('merch', 0.5440044403076172),

('actoresau', 0.5389758944511414)]Many of these are words very close in meaning to “actress”: actor (actor), actores (actress), actorion (actors), berfformwraig (female performer), comediwraig and digrifwraig (female comedian), sgriptwraig (female script writer), athletwraig (female athlete), merch (girl or daughter), and actoresau (actresses).

This is just one example of a grammatical relationship between words, gender swapping. Other relationships that can be tested include verb conjugations, adjectives and their superlatives, plurals, and even countries and their nationalities. A grammatical relationship we tested that is specific to the Welsh language was equivalent words in South and North Wales dialects.

We automated this testing and evaluation process on a large number of standardised examples in order to obtain quantitative evaluation statistics to compare the models. Part of the work was in fact to develop standardised lists of comparable words and grammatical structures for use in Welsh for the first time. Other evaluation tasks included using the word embeddings to identify synonyms, and word clustering tasks. However, smaller scale qualitative evaluation from a native Welsh speaker (me!) was also a vital part of the evaluation.

What’s the point?

Including word embeddings as parts of other natural language processing (NLP) tasks has shown to improve their performances, especially on low resource languages were training data might be hard to come by. One reason is because word embeddings help the models ‘understand’ words they have never seen before in the training data.

Taking this idea further, models of low resource languages can benefit from cross-lingual word embeddings, leveraging the greater quality understanding from a second well resourced language. Cross-lingual word embeddings are a mapping from the words of two languages into a shared vector space, kept together but separate. This can be thought of as ‘aligning’ two sets of word embeddings from two different languages. Therefore an NLP model of a low resource language could be trained solely on data from a well resourced language!

We trained English-Welsh cross-lingual word embeddings, available here: https://github.com/cardiffnlp/en-cy-bilingual-embeddings.

Also here are instructions for training a cross-lingual sentiment analysis model. A sentiment analysis model is a supervised machine learning model that predicts a sentence’s sentiment (positive, neutral, negative). This one can be trained solely on English language data, in this case IMDB reviews, but can be used on Welsh language tasks, despite not having seen Welsh language training data!